Architecture Informatique Materielle - S5

Annee: 2022-2023 (Semestre 5)

Credits: 3 ECTS

Type: Informatique / Architecture des Systemes

PART A: PRESENTATION GENERALE

Objectifs du cours

Le cours "Architecture Informatique Materielle" fournit une comprehension approfondie de l'organisation et du fonctionnement des systemes informatiques au niveau materiel. Il couvre l'ensemble de la hierarchie memoire, de l'architecture des processeurs, et des mecanismes d'optimisation des performances. Ce cours est fondamental pour comprendre comment le materiel influence les performances logicielles et pour concevoir des systemes embarques efficaces.

Competences visees

- Maitriser les concepts d'architecture des processeurs (RISC, pipeline, unites fonctionnelles)

- Comprendre la hierarchie memoire (memoire physique, virtuelle, caches)

- Analyser les performances des systemes informatiques

- Programmer en assembleur MIPS pour le bas niveau

- Optimiser le code en fonction de l'architecture materielle

- Comprendre les mecanismes de pagination et de gestion memoire

Organisation

- Volume horaire: 30h (CM: 18h, TD: 12h)

- Evaluation: Examen ecrit + TDs notes + TP assembleur

- Semestre: 5 (2022-2023)

- Prerequis: Logique sequentielle, systemes numeriques

PART B: EXPERIENCE, CONTEXTE ET FONCTION

Contenu pedagogique

1. Introduction Generale aux Architectures

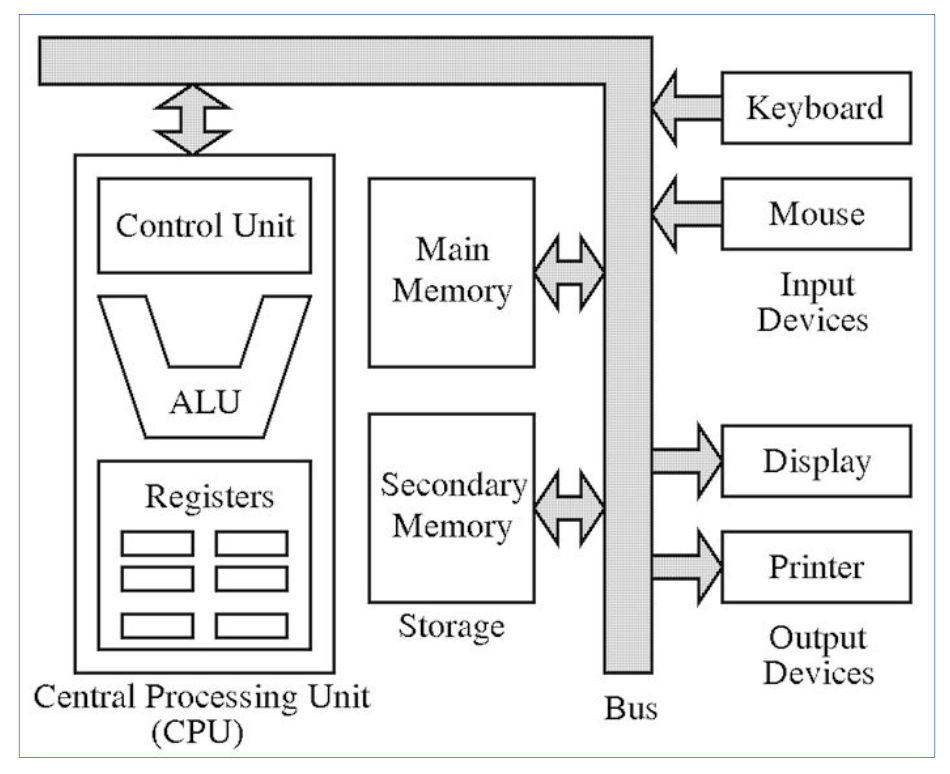

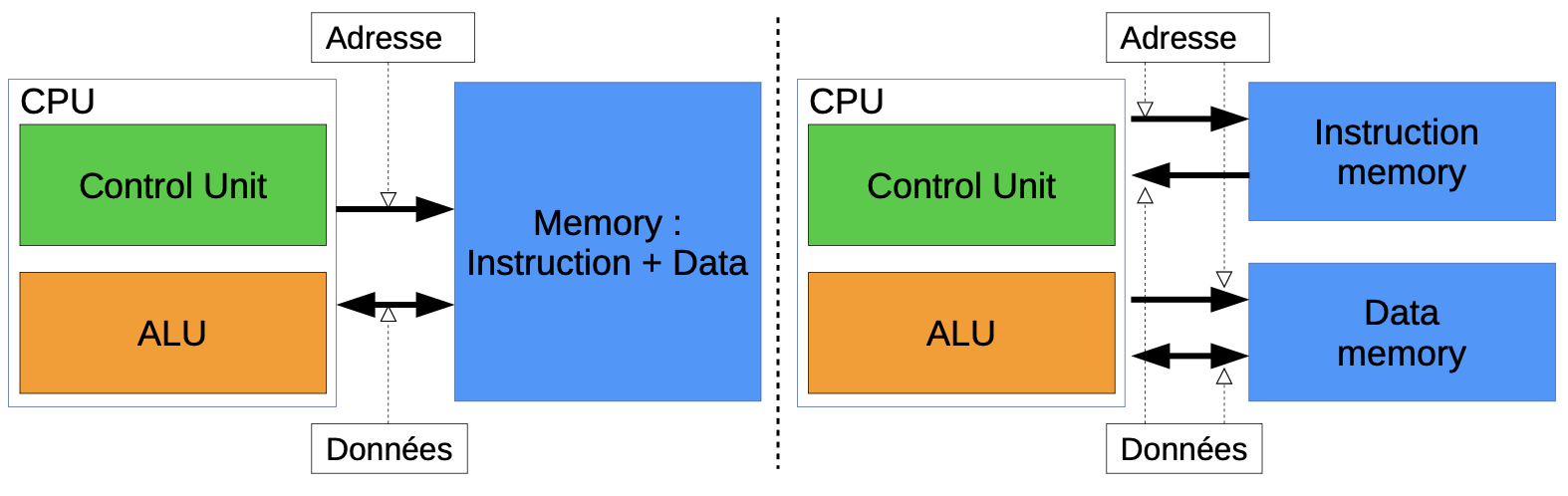

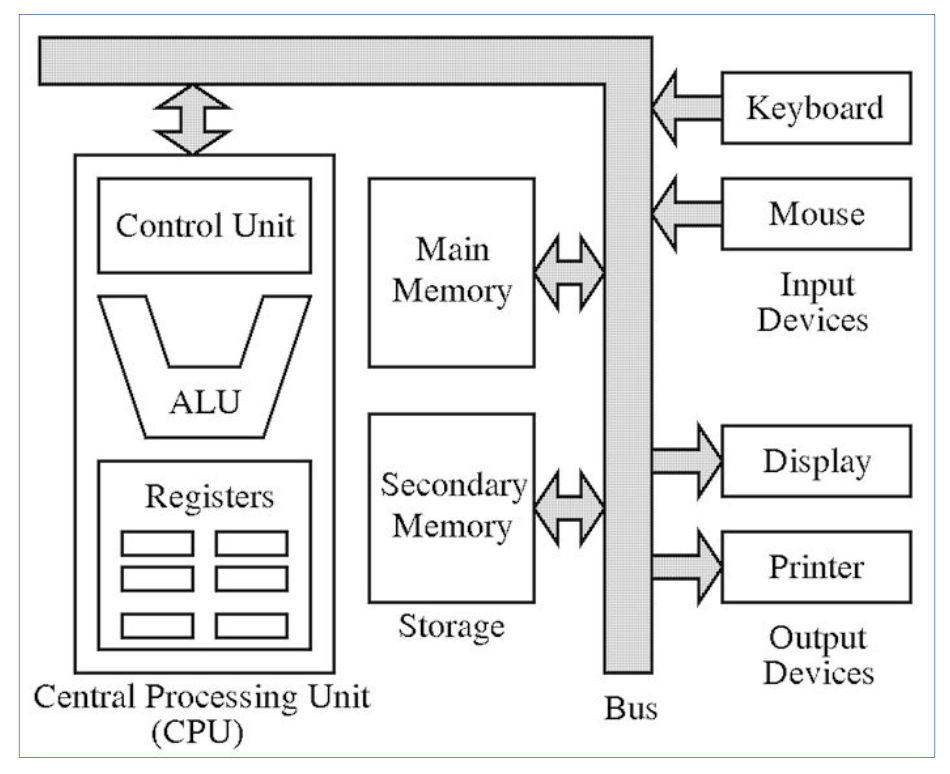

Concepts fondamentaux:

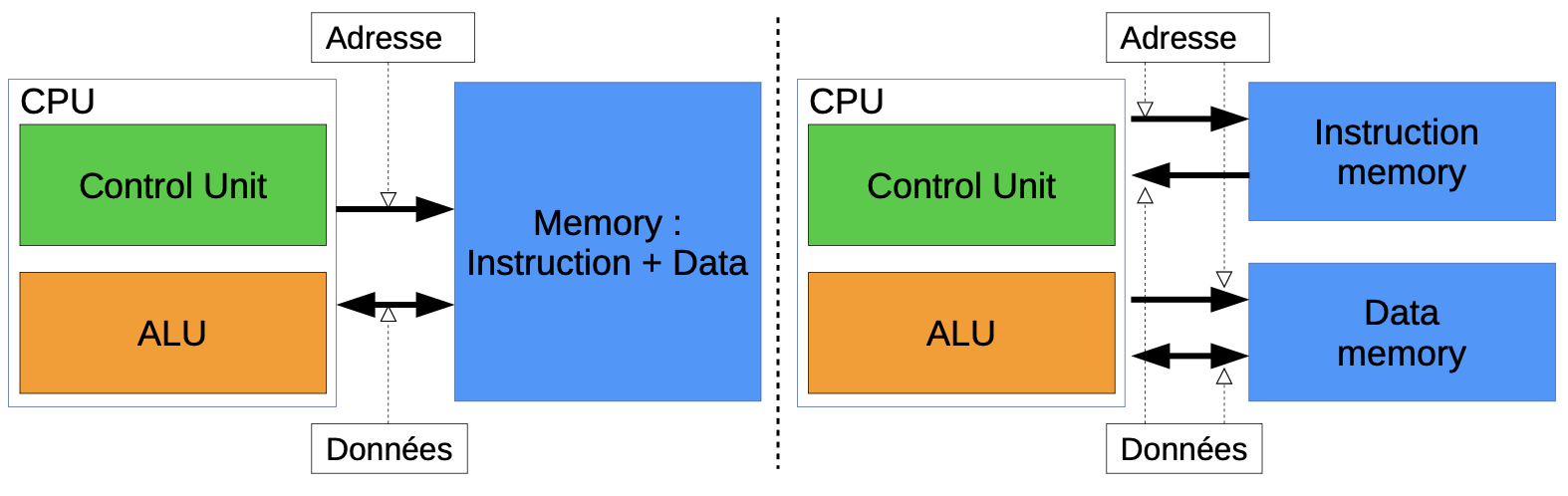

- Architecture de Von Neumann vs Harvard

- Modele de Von Neumann: memoire unique pour donnees et instructions

- Architecture Harvard: separation physique instructions/donnees

- Bus systeme: adresses, donnees, controle

- Cycle d'execution: Fetch-Decode-Execute

Evolution historique:

- Des premiers ordinateurs aux architectures modernes

- Loi de Moore et ses limites actuelles

- Passage du monoprocesseur au multiprocesseur

- Architectures RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) vs CISC (Complex)

Mesure de performances:

- CPI (Cycles Per Instruction)

- MIPS (Millions d'Instructions Per Second)

- Temps d'execution CPU

- Benchmark et profiling

Supports de cours: Introduction generale aux architectures (PDF)

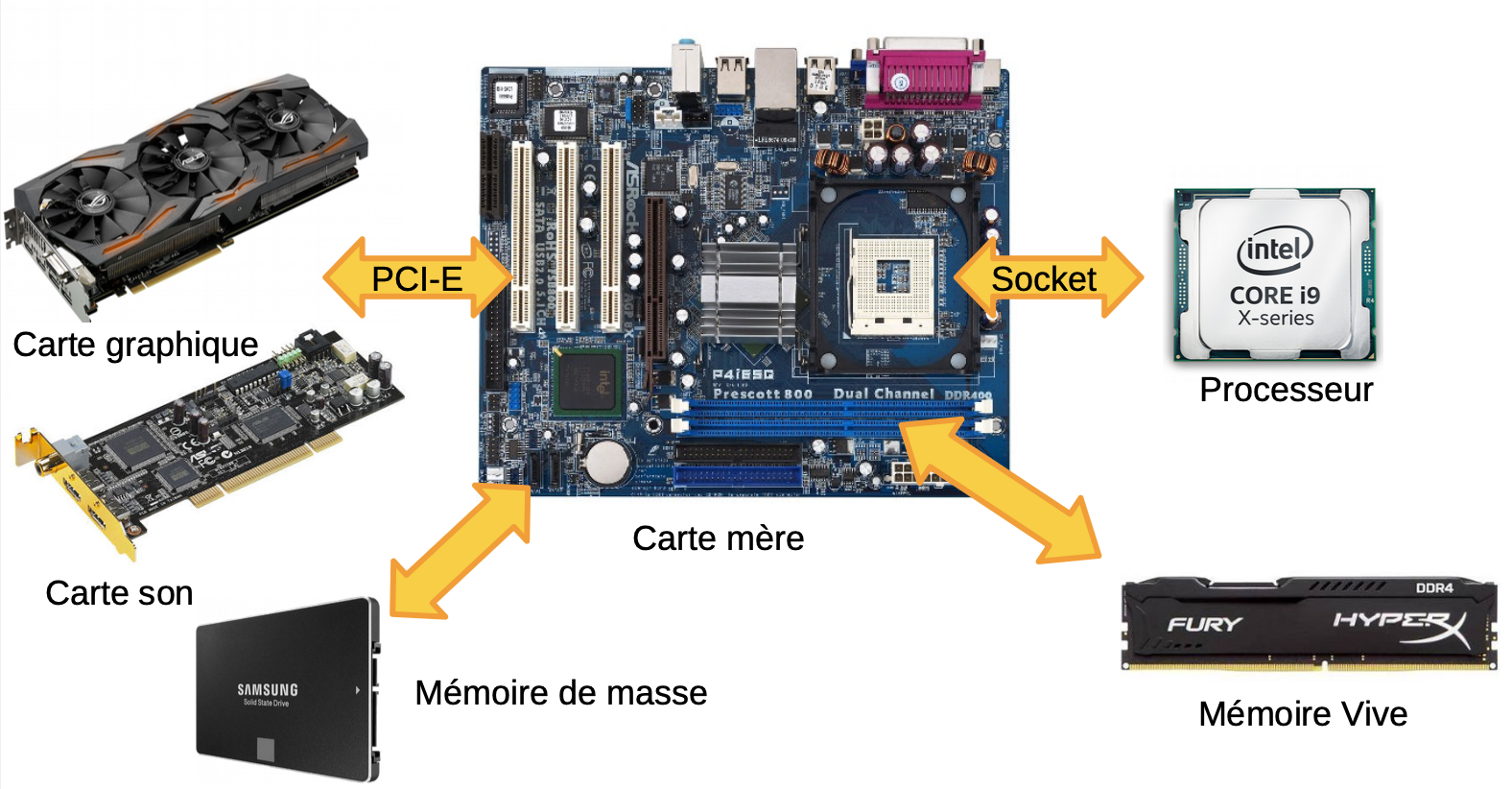

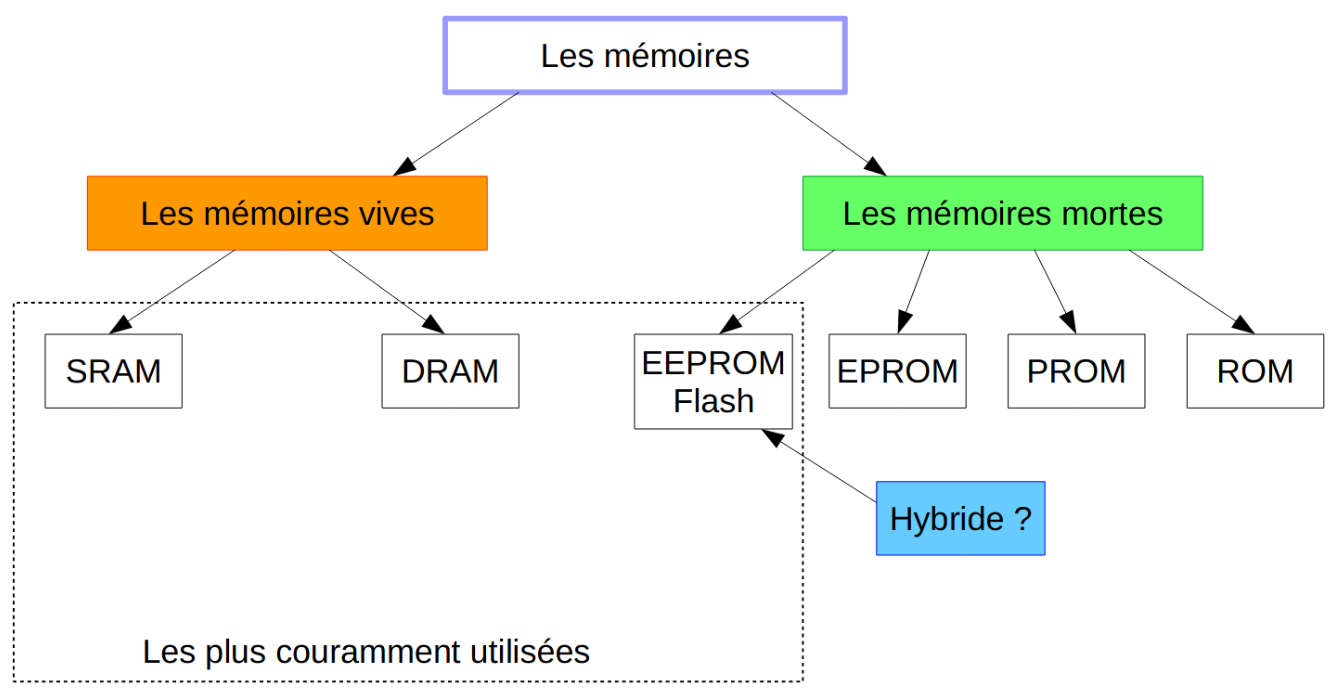

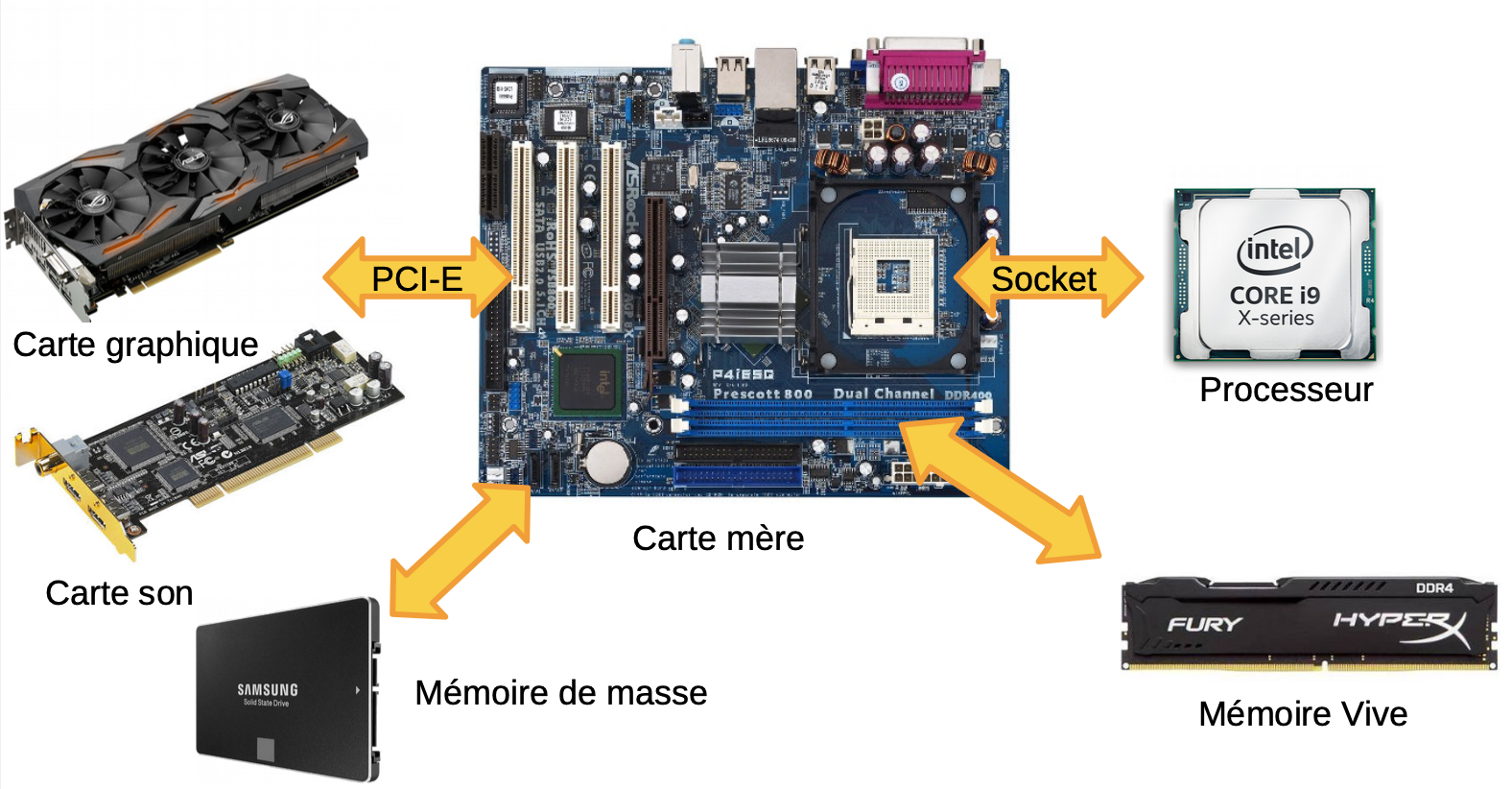

2. Memoire Physique

Figure : Architecture Von Neumann - Modele classique avec bus partages

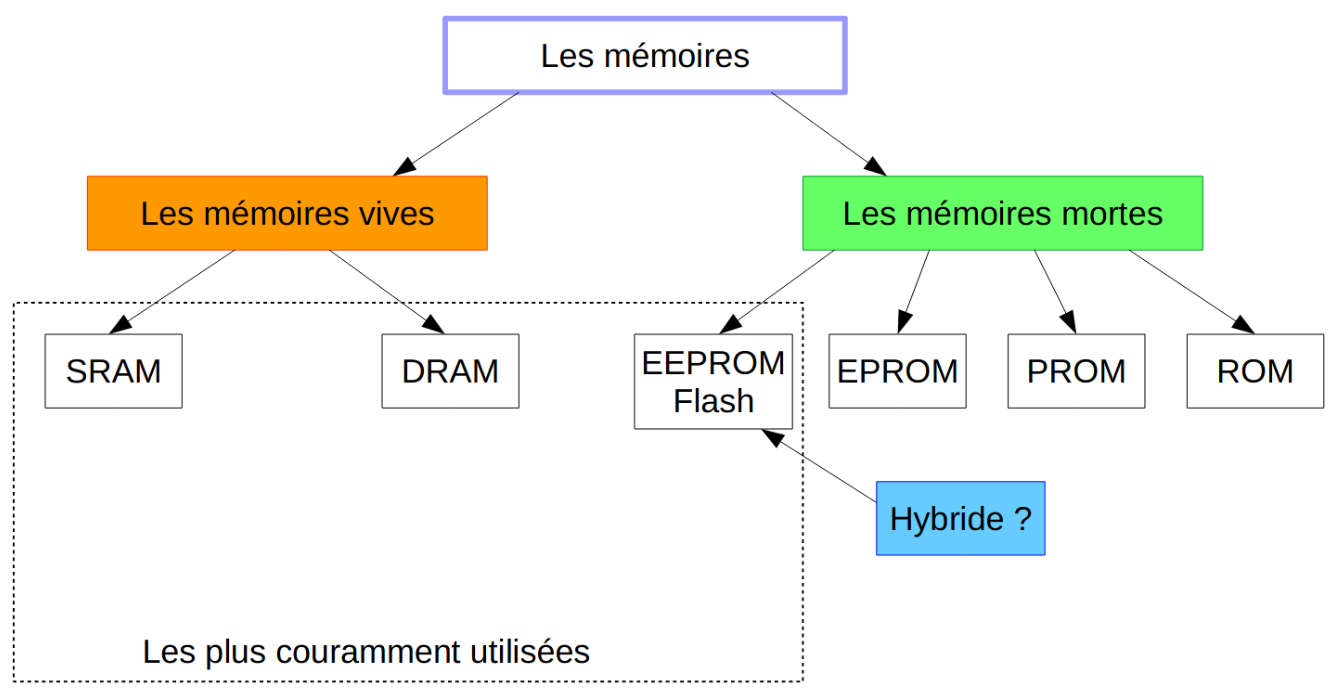

Organisation memoire:

- Hierarchie memoire: registres → cache → RAM → disque

- Technologies memoire: SRAM, DRAM, ROM, Flash

- Temps d'acces et bande passante

- Principe de localite (temporelle et spatiale)

Adressage memoire:

- Espace d'adressage lineaire

- Adressage par mot vs par octet (byte-addressable)

- Alignement memoire et padding

- Endianness (big-endian vs little-endian)

Organisation des donnees:

Exemple d'organisation memoire 32 bits:

Adresse | Contenu (hex)

-----------|-----------------

0x00000000 | 0xAABBCCDD

0x00000004 | 0x11223344

0x00000008 | 0xFFFF0000

Supports de cours: Memoire physique (PDF)

3. Memoire Virtuelle

Concepts de virtualisation:

- Separation adresse virtuelle / adresse physique

- Espace d'adressage par processus

- Protection memoire et isolation

- Partage de memoire entre processus

Mecanisme de pagination:

- Pages virtuelles et cadres physiques (frames)

- Taille de page typique: 4 KB, 2 MB (large pages)

- Table des pages (page table)

- TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer): cache pour traductions

Formules de traduction:

Adresse virtuelle = Numero de page virtuelle + Offset

Adresse physique = Numero de cadre physique + Offset

Exemple avec pages de 4 KB (2^12 octets):

Adresse virtuelle: 32 bits

- 20 bits: numero de page (2^20 pages)

- 12 bits: offset dans la page (4096 octets)

Gestion des defauts de page:

- Page fault (defaut de page)

- Algorithmes de remplacement: LRU, FIFO, Clock

- Swapping et pagination a la demande

- Working set et thrashing

Table des pages multi-niveaux:

- Table des pages sur 2 niveaux (x86)

- Table des pages sur 3/4 niveaux (x86-64)

- Reduction de l'espace memoire pour les tables

- Pagination inverse

Supports de cours: Memoire virtuelle (PDF)

4. Memoires Caches

Principe du cache:

- Cache situe entre CPU et RAM

- Exploite la localite spatiale et temporelle

- Reduction du temps d'acces moyen

- Hierarchie: L1 (le plus rapide), L2, L3

Organisation du cache:

Cache a correspondance directe (direct-mapped):

Adresse memoire decomposee en:

Tag | Index | Offset

Exemple: cache 16 KB, lignes de 64 octets

Offset: 6 bits (64 = 2^6)

Index: 8 bits (256 lignes)

Tag: 18 bits (pour adresse 32 bits)

Cache associatif par ensemble (set-associative):

- N-way set-associative (2-way, 4-way, 8-way)

- Compromis entre direct-mapped et fully associative

- Politique de remplacement: LRU, Random, FIFO

Formules de performances:

Temps d'acces moyen = Hit_time + Miss_rate x Miss_penalty

Taux de hit (hit rate) = Nombre de hits / Nombre total d'acces

Taux de miss (miss rate) = 1 - Hit rate

Exemple:

Hit time = 1 cycle

Miss penalty = 100 cycles

Miss rate = 2%

Temps moyen = 1 + 0.02 x 100 = 3 cycles

Types de miss:

- Compulsory miss (cold miss): premier acces

- Capacity miss: cache trop petit

- Conflict miss: collision dans direct-mapped

Coherence de cache:

- Probleme en multiprocesseur

- Protocoles MESI, MOESI

- Write-through vs write-back

- Invalidation vs mise a jour

Supports de cours: Les caches (PDF)

5. Architecture du Processeur

Processeur RISC (MIPS):

- Jeu d'instructions reduit et regulier

- Instructions de taille fixe (32 bits)

- Load/Store architecture

- Pipeline efficace

Registres MIPS:

$zero ($0): toujours 0

$at ($1): reserve assembleur

$v0-$v1 ($2-$3): valeurs de retour

$a0-$a3 ($4-$7): arguments de fonction

$t0-$t9 ($8-$15, $24-$25): temporaires

$s0-$s7 ($16-$23): sauvegardes

$k0-$k1 ($26-$27): reserves OS

$gp ($28): pointeur global

$sp ($29): pointeur de pile

$fp ($30): pointeur de cadre

$ra ($31): adresse de retour

Formats d'instructions:

Format R (Register): operations arithmetiques/logiques

| op (6) | rs (5) | rt (5) | rd (5) | shamt (5) | funct (6) |

Exemple: add $13, $11, $12

Format I (Immediate): load/store, branches, constantes

| op (6) | rs (5) | rt (5) | immediate (16) |

Exemple: addi $10, $zero, 53

Format J (Jump): sauts inconditionnels

| op (6) | address (26) |

Exemple: j add_32bits

Pipeline du processeur:

- IF (Instruction Fetch): chargement instruction

- ID (Instruction Decode): decodage et lecture registres

- EX (Execute): execution ALU

- MEM (Memory): acces memoire (load/store)

- WB (Write Back): ecriture resultat dans registre

Aleas de pipeline (hazards):

- Aleas de donnees: RAW (Read After Write), WAR, WAW

- Aleas de controle: branches et sauts

- Aleas structurels: conflits de ressources

Solutions aux aleas:

- Forwarding (court-circuit)

- Stall (bulles dans le pipeline)

- Branch prediction (prediction de branchement)

- Delayed branch

Supports de cours: Architecture du processeur (PDF)

PART C: ASPECTS TECHNIQUES

Cette section presente les elements techniques appris a travers les TPs et exercices pratiques.

Programmation Assembleur MIPS

TP1: Addition 32 bits et Conversion de Temps

Code assembleur realise:

# Initialisation des variables

addi $10, $zero, 53 # Secondes = 53

addi $1, $zero, 27 # Minutes = 27

addi $2, $zero, 3 # Heures = 3

j add_32bits # Saut vers fonction addition

# Conversion temps en secondes totales

conv_secondes:

addi $4, $zero, 3600 # $4 = 3600 (secondes/heure)

addi $5, $zero, 60 # $5 = 60 (secondes/minute)

mul $6, $2, $4 # $6 = heures x 3600

mul $7, $1, $5 # $7 = minutes x 60

add $8, $7, $6 # $8 = (heures x 3600) + (minutes x 60)

add $9, $8, $10 # $9 = total + secondes

# Addition 32 bits avec detection de depassement

add_32bits:

lw $11, var # Charger variable a

lw $12, var # Charger variable b

addu $13, $12, $11 # c = a + b (addition non signee)

and $14, $11, $12 # e = a AND b (retenue entrante)

xor $15, $11, $12 # x = a XOR b (somme sans retenue)

not $18, $13 # Inversion de c

and $16, $18, $15 # x AND (NOT c)

or $17, $16, $14 # Calcul du bit de retenue sortante

srl $21, $17, 31 # Decalage pour extraire bit de poids fort

# $21 contient le flag de depassement (overflow)

var: .word 0xFFFF0000 # Variable de test 32 bits

Concepts appliques:

- Instructions arithmetiques:

addi: addition immediate (avec constante)add/addu: addition signee / non signeemul: multiplication

- Instructions logiques:

and: ET bit a bitor: OU bit a bitxor: OU exclusif bit a bitnot: inversion (complement a 1)

- Instructions memoire:

lw(load word): chargement 32 bits depuis memoire- Directive

.word: declaration de donnee 32 bits

- Instructions de controle:

j(jump): saut inconditionnel- Etiquettes pour les adresses

- Gestion du depassement:

- Detection de l'overflow sur addition

- Utilisation de la logique booleenne pour calculer la retenue

- Formule:

Overflow = Cout XOR Cin(retenue sortante XOR entrante)

Analyse de l'algorithme de detection de depassement

Principe mathematique:

Pour detecter un depassement (overflow) sur addition:

c = a + b

e = a AND b (positions ou a=1 et b=1, retenue garantie)

x = a XOR b (somme sans retenue)

Retenue sortante = (x AND NOT(c)) OR e

Si le bit de poids fort de la retenue = 1 → overflow

Exemple numerique:

a = 0xFFFF0000 (grand nombre negatif en complement a 2)

b = 0xFFFF0000

c = 0xFFFE0000 (resultat)

Analyse bit par bit du MSB (bit 31):

a[31] = 1, b[31] = 1

c[31] = 1

Overflow detecte si signe change incorrectement

Exercices de Calcul de Performances

Calcul du temps d'execution

Formule fondamentale:

Temps_CPU = Nombre_instructions x CPI x Periode_horloge

Ou:

CPI = Cycles Per Instruction

Periode = 1 / Frequence

Exemple d'exercice:

Programme: 1 million d'instructions

CPI moyen: 2.5

Frequence CPU: 2 GHz

Temps_CPU = 10^6 x 2.5 x (1 / 2x10^9)

= 2.5x10^6 / 2x10^9

= 1.25 ms

Performances du cache

Exercice type:

Cache L1: 32 KB, 4-way associative, ligne 64 octets

Hit time: 1 cycle

Hit rate: 95%

RAM:

Latence: 100 cycles

Calcul temps d'acces moyen:

T_moy = 0.95 x 1 + 0.05 x 100

= 0.95 + 5

= 5.95 cycles

Amelioration par rapport a sans cache:

Speedup = 100 / 5.95 = 16.8x

Calcul de pagination

Exercice de traduction d'adresse:

Configuration:

- Pages de 4 KB (4096 octets = 2^12)

- Adresses virtuelles 32 bits

- Adresse physique 30 bits

Adresse virtuelle: 0x12345678

Decomposition:

Bits 31-12: numero page virtuelle = 0x12345

Bits 11-0: offset = 0x678

Si table des pages indique: VPN 0x12345 → PFN 0x00ABC

Adresse physique:

= (0x00ABC << 12) | 0x678

= 0x00ABC678

Optimisation du Code

Exploitation du cache

Mauvaise utilisation (cache miss frequents):

// Parcours colonne par colonne (mauvaise localite spatiale)

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++)

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

sum += matrix[i][j]; // Acces non contigus

Bonne utilisation (cache friendly):

// Parcours ligne par ligne (bonne localite spatiale)

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++)

sum += matrix[i][j]; // Acces contigus

Explication:

- Les matrices en C sont stockees ligne par ligne (row-major order)

- Lignes de cache: 64 octets = 16 entiers (4 octets chacun)

- Parcours ligne → tous les elements d'une ligne charges ensemble

- Parcours colonne → chaque acces charge une nouvelle ligne de cache

Blocking/Tiling pour matrices

Technique de blocking:

// Multiplication matricielle avec blocking

#define BLOCK_SIZE 32

for (int ii = 0; ii < N; ii += BLOCK_SIZE)

for (int jj = 0; jj < N; jj += BLOCK_SIZE)

for (int kk = 0; kk < N; kk += BLOCK_SIZE)

// Bloc de BLOCK_SIZE x BLOCK_SIZE

for (int i = ii; i < min(ii+BLOCK_SIZE, N); i++)

for (int j = jj; j < min(jj+BLOCK_SIZE, N); j++)

for (int k = kk; k < min(kk+BLOCK_SIZE, N); k++)

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j];

Avantage: reutilisation des donnees en cache L1 avant eviction

PART D: ANALYSE ET REFLEXION

Connaissances et competences mobilisees

- Architecture des systemes: comprehension profonde du fonctionnement materiel

- Programmation bas niveau: maitrise de l'assembleur MIPS

- Optimisation: capacite a ecrire du code efficace tenant compte du materiel

- Analyse de performances: calcul et optimisation des performances systeme

- Gestion memoire: comprehension des mecanismes de pagination et cache

Auto-evaluation

Ce cours a ete fondamental pour ma comprehension des systemes informatiques. J'ai particulierement apprecie:

Points forts:

- Lien theorie/pratique: les TPs en assembleur MIPS ont rendu concrets les concepts abstraits

- Comprehension du materiel: vision claire de ce qui se passe "sous le capot"

- Optimisation: capacite a comprendre pourquoi certains codes sont plus rapides

- Debogage: meilleure comprehension des erreurs (segfault, cache miss, etc.)

Difficultes rencontrees:

- Assembleur MIPS: syntaxe et conventions differentes du C

- Pipeline et hazards: concepts abstraits necessitant de la visualisation

- Calculs de cache: nombreuses formules et cas particuliers

Applications pratiques:

- Optimisation de code pour systemes embarques

- Comprehension des contraintes temps reel

- Choix d'algorithmes adaptes a l'architecture

Mon opinion

Ce cours est indispensable pour tout ingenieur en informatique ou systemes embarques. Meme a l'ere des langages de haut niveau, comprendre l'architecture materielle permet:

- Meilleure performance: code optimise pour le cache et le pipeline

- Debugging efficace: comprendre les erreurs memoire, les ralentissements

- Choix techniques: selectionner le bon processeur pour une application

- Embarque: conception de systemes avec contraintes strictes

Connexions avec autres cours:

- Systemes d'exploitation (S5): gestion memoire virtuelle, ordonnancement

- Microcontroleur (S6): application pratique sur STM32

- Temps Reel (S8): contraintes de timing liees au materiel

- Systemes embarques (S7): optimisation pour ressources limitees

Evolution des architectures:

Aujourd'hui, les defis ont evolue:

- Multiprocesseur: parallelisme, coherence cache complexe

- Heterogene: CPU + GPU + accelerateurs (TPU, NPU)

- Memoire non-volatile: nouvelles technologies (3D XPoint, ReRAM)

- Securite: Spectre, Meltdown → compromis performance/securite

La loi de Moore ralentit, mais l'innovation continue:

- Architecture 3D (empilement)

- Memoires proches du calcul (in-memory computing)

- Architectures neuromorphiques

- Calcul quantique (futur)

Recommandations pour bien reussir:

- Pratiquer l'assembleur: ecrire du code MIPS, analyser le desassemblage C

- Visualiser: dessiner les pipelines, les caches, les tables de pages

- Calculer: faire et refaire les exercices de performances

- Lire les specifications: datasheets de processeurs (ARM, x86)

- Profiler: utiliser des outils (perf, valgrind) pour observer le cache

Applications professionnelles:

Ces connaissances sont utilisees dans:

- Developpement de compilateurs: optimisations machine-specifiques

- Systemes d'exploitation: schedulers, gestionnaires memoire

- Jeux video: optimisations poussees pour FPS eleves

- HPC (High Performance Computing): supercalculateurs

- IoT: microcontroleurs a ressources limitees

- Automobile: ECU temps reel critiques

- Securite: analyse de vulnerabilites hardware

En conclusion, ce cours fournit les bases essentielles pour comprendre comment le logiciel interagit avec le materiel. C'est un investissement qui porte ses fruits tout au long de la carriere, car les principes fondamentaux (hierarchie memoire, pipeline, cache) restent valables meme si les technologies evoluent.

Documents de Cours

Voici les supports de cours en PDF pour approfondir l'architecture informatique materielle :

Introduction aux Architectures

Vue d'ensemble des architectures informatiques, evolution historique et concepts fondamentaux.

Memoire Physique

Organisation de la memoire physique, types de memoires (RAM, ROM, Flash) et hierarchie memoire.

Memoire Virtuelle

Gestion de la memoire virtuelle, pagination, segmentation et traduction d'adresses.

Memoires Caches

Fonctionnement des caches, politiques de remplacement, coherence des caches et optimisation des performances.

Processeur

Architecture du processeur, pipeline, parallelisme d'instructions et optimisations materielles.

Computer Hardware Architecture - S5

Year: 2022-2023 (Semester 5)

Credits: 3 ECTS

Type: Computer Science / System Architecture

PART A: GENERAL OVERVIEW

Course Objectives

The "Computer Hardware Architecture" course provides an in-depth understanding of the organization and operation of computer systems at the hardware level. It covers the entire memory hierarchy, processor architecture, and performance optimization mechanisms. This course is fundamental for understanding how hardware influences software performance and for designing efficient embedded systems.

Targeted Skills

- Master processor architecture concepts (RISC, pipeline, functional units)

- Understand the memory hierarchy (physical memory, virtual memory, caches)

- Analyze computer system performance

- Program in MIPS assembly for low-level operations

- Optimize code based on the hardware architecture

- Understand pagination and memory management mechanisms

Organization

- Course hours: 30h (Lectures: 18h, Tutorials: 12h)

- Assessment: Written exam + Graded tutorials + Assembly lab

- Semester: 5 (2022-2023)

- Prerequisites: Sequential logic, digital systems

PART B: EXPERIENCE, CONTEXT AND PURPOSE

Course Content

1. General Introduction to Architectures

Fundamental concepts:

- Von Neumann vs Harvard architecture

- Von Neumann model: single memory for data and instructions

- Harvard architecture: physical separation of instructions/data

- System bus: addresses, data, control

- Execution cycle: Fetch-Decode-Execute

Historical evolution:

- From early computers to modern architectures

- Moore's Law and its current limitations

- Transition from single-processor to multi-processor

- RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) vs CISC (Complex) architectures

Performance measurement:

- CPI (Cycles Per Instruction)

- MIPS (Millions of Instructions Per Second)

- CPU execution time

- Benchmarking and profiling

Course materials: General introduction to architectures (PDF)

2. Physical Memory

Figure: Von Neumann Architecture - Classic model with shared buses

Memory organization:

- Memory hierarchy: registers → cache → RAM → disk

- Memory technologies: SRAM, DRAM, ROM, Flash

- Access time and bandwidth

- Locality principle (temporal and spatial)

Memory addressing:

- Linear address space

- Word-addressable vs byte-addressable

- Memory alignment and padding

- Endianness (big-endian vs little-endian)

Data organization:

32-bit memory organization example:

Address | Content (hex)

-----------|-----------------

0x00000000 | 0xAABBCCDD

0x00000004 | 0x11223344

0x00000008 | 0xFFFF0000

Course materials: Physical memory (PDF)

3. Virtual Memory

Virtualization concepts:

- Separation of virtual address / physical address

- Per-process address space

- Memory protection and isolation

- Memory sharing between processes

Paging mechanism:

- Virtual pages and physical frames

- Typical page size: 4 KB, 2 MB (large pages)

- Page table

- TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer): cache for address translations

Translation formulas:

Virtual address = Virtual page number + Offset

Physical address = Physical frame number + Offset

Example with 4 KB pages (2^12 bytes):

Virtual address: 32 bits

- 20 bits: page number (2^20 pages)

- 12 bits: offset within the page (4096 bytes)

Page fault handling:

- Page fault

- Replacement algorithms: LRU, FIFO, Clock

- Swapping and demand paging

- Working set and thrashing

Multi-level page tables:

- 2-level page table (x86)

- 3/4-level page table (x86-64)

- Reducing memory space for tables

- Inverted page table

Course materials: Virtual memory (PDF)

4. Cache Memory

Cache principle:

- Cache located between CPU and RAM

- Exploits spatial and temporal locality

- Reduces average access time

- Hierarchy: L1 (fastest), L2, L3

Cache organization:

Direct-mapped cache:

Memory address decomposed into:

Tag | Index | Offset

Example: 16 KB cache, 64-byte lines

Offset: 6 bits (64 = 2^6)

Index: 8 bits (256 lines)

Tag: 18 bits (for 32-bit address)

Set-associative cache:

- N-way set-associative (2-way, 4-way, 8-way)

- Compromise between direct-mapped and fully associative

- Replacement policy: LRU, Random, FIFO

Performance formulas:

Average access time = Hit_time + Miss_rate x Miss_penalty

Hit rate = Number of hits / Total number of accesses

Miss rate = 1 - Hit rate

Example:

Hit time = 1 cycle

Miss penalty = 100 cycles

Miss rate = 2%

Average time = 1 + 0.02 x 100 = 3 cycles

Types of misses:

- Compulsory miss (cold miss): first access

- Capacity miss: cache too small

- Conflict miss: collision in direct-mapped

Cache coherence:

- Multiprocessor challenge

- MESI, MOESI protocols

- Write-through vs write-back

- Invalidation vs update

Course materials: Caches (PDF)

5. Processor Architecture

RISC Processor (MIPS):

- Reduced and regular instruction set

- Fixed-size instructions (32 bits)

- Load/Store architecture

- Efficient pipeline

MIPS Registers:

$zero ($0): always 0

$at ($1): reserved for assembler

$v0-$v1 ($2-$3): return values

$a0-$a3 ($4-$7): function arguments

$t0-$t9 ($8-$15, $24-$25): temporaries

$s0-$s7 ($16-$23): saved registers

$k0-$k1 ($26-$27): reserved for OS

$gp ($28): global pointer

$sp ($29): stack pointer

$fp ($30): frame pointer

$ra ($31): return address

Instruction formats:

R-format (Register): arithmetic/logic operations

| op (6) | rs (5) | rt (5) | rd (5) | shamt (5) | funct (6) |

Example: add $13, $11, $12

I-format (Immediate): load/store, branches, constants

| op (6) | rs (5) | rt (5) | immediate (16) |

Example: addi $10, $zero, 53

J-format (Jump): unconditional jumps

| op (6) | address (26) |

Example: j add_32bits

Processor pipeline:

- IF (Instruction Fetch): load instruction

- ID (Instruction Decode): decode and read registers

- EX (Execute): ALU execution

- MEM (Memory): memory access (load/store)

- WB (Write Back): write result to register

Pipeline hazards:

- Data hazards: RAW (Read After Write), WAR, WAW

- Control hazards: branches and jumps

- Structural hazards: resource conflicts

Hazard solutions:

- Forwarding (bypassing)

- Stalling (pipeline bubbles)

- Branch prediction

- Delayed branch

Course materials: Processor architecture (PDF)

PART C: TECHNICAL ASPECTS

This section presents the technical elements learned through lab sessions and practical exercises.

MIPS Assembly Programming

Lab 1: 32-bit Addition and Time Conversion

Assembly code written:

# Variable initialization

addi $10, $zero, 53 # Seconds = 53

addi $1, $zero, 27 # Minutes = 27

addi $2, $zero, 3 # Hours = 3

j add_32bits # Jump to addition function

# Time conversion to total seconds

conv_secondes:

addi $4, $zero, 3600 # $4 = 3600 (seconds/hour)

addi $5, $zero, 60 # $5 = 60 (seconds/minute)

mul $6, $2, $4 # $6 = hours x 3600

mul $7, $1, $5 # $7 = minutes x 60

add $8, $7, $6 # $8 = (hours x 3600) + (minutes x 60)

add $9, $8, $10 # $9 = total + seconds

# 32-bit addition with overflow detection

add_32bits:

lw $11, var # Load variable a

lw $12, var # Load variable b

addu $13, $12, $11 # c = a + b (unsigned addition)

and $14, $11, $12 # e = a AND b (incoming carry)

xor $15, $11, $12 # x = a XOR b (sum without carry)

not $18, $13 # Invert c

and $16, $18, $15 # x AND (NOT c)

or $17, $16, $14 # Compute outgoing carry bit

srl $21, $17, 31 # Shift to extract most significant bit

# $21 contains the overflow flag

var: .word 0xFFFF0000 # 32-bit test variable

Applied concepts:

- Arithmetic instructions:

addi: immediate addition (with constant)add/addu: signed / unsigned additionmul: multiplication

- Logical instructions:

and: bitwise ANDor: bitwise ORxor: bitwise exclusive ORnot: inversion (one's complement)

- Memory instructions:

lw(load word): 32-bit load from memory.worddirective: 32-bit data declaration

- Control instructions:

j(jump): unconditional jump- Labels for addresses

- Overflow handling:

- Overflow detection on addition

- Using Boolean logic to compute the carry

- Formula:

Overflow = Cout XOR Cin(outgoing carry XOR incoming carry)

Analysis of the Overflow Detection Algorithm

Mathematical principle:

To detect overflow on addition:

c = a + b

e = a AND b (positions where a=1 and b=1, guaranteed carry)

x = a XOR b (sum without carry)

Outgoing carry = (x AND NOT(c)) OR e

If the most significant bit of the carry = 1 → overflow

Numerical example:

a = 0xFFFF0000 (large negative number in two's complement)

b = 0xFFFF0000

c = 0xFFFE0000 (result)

Bit-by-bit analysis of MSB (bit 31):

a[31] = 1, b[31] = 1

c[31] = 1

Overflow detected if sign changes incorrectly

Performance Calculation Exercises

Execution Time Calculation

Fundamental formula:

CPU_Time = Number_of_instructions x CPI x Clock_period

Where:

CPI = Cycles Per Instruction

Period = 1 / Frequency

Exercise example:

Program: 1 million instructions

Average CPI: 2.5

CPU frequency: 2 GHz

CPU_Time = 10^6 x 2.5 x (1 / 2x10^9)

= 2.5x10^6 / 2x10^9

= 1.25 ms

Cache Performance

Typical exercise:

L1 Cache: 32 KB, 4-way associative, 64-byte line

Hit time: 1 cycle

Hit rate: 95%

RAM:

Latency: 100 cycles

Average access time calculation:

T_avg = 0.95 x 1 + 0.05 x 100

= 0.95 + 5

= 5.95 cycles

Improvement compared to no cache:

Speedup = 100 / 5.95 = 16.8x

Paging Calculation

Address translation exercise:

Configuration:

- 4 KB pages (4096 bytes = 2^12)

- 32-bit virtual addresses

- 30-bit physical address

Virtual address: 0x12345678

Decomposition:

Bits 31-12: virtual page number = 0x12345

Bits 11-0: offset = 0x678

If page table indicates: VPN 0x12345 → PFN 0x00ABC

Physical address:

= (0x00ABC << 12) | 0x678

= 0x00ABC678

Code Optimization

Cache Exploitation

Poor usage (frequent cache misses):

// Column-by-column traversal (poor spatial locality)

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++)

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

sum += matrix[i][j]; // Non-contiguous accesses

Good usage (cache friendly):

// Row-by-row traversal (good spatial locality)

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++)

sum += matrix[i][j]; // Contiguous accesses

Explanation:

- Matrices in C are stored row by row (row-major order)

- Cache lines: 64 bytes = 16 integers (4 bytes each)

- Row traversal → all elements of a row loaded together

- Column traversal → each access loads a new cache line

Blocking/Tiling for Matrices

Blocking technique:

// Matrix multiplication with blocking

#define BLOCK_SIZE 32

for (int ii = 0; ii < N; ii += BLOCK_SIZE)

for (int jj = 0; jj < N; jj += BLOCK_SIZE)

for (int kk = 0; kk < N; kk += BLOCK_SIZE)

// Block of BLOCK_SIZE x BLOCK_SIZE

for (int i = ii; i < min(ii+BLOCK_SIZE, N); i++)

for (int j = jj; j < min(jj+BLOCK_SIZE, N); j++)

for (int k = kk; k < min(kk+BLOCK_SIZE, N); k++)

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j];

Advantage: reuse of data in L1 cache before eviction

PART D: ANALYSIS AND REFLECTION

Knowledge and Skills Mobilized

- System architecture: deep understanding of hardware operation

- Low-level programming: mastery of MIPS assembly

- Optimization: ability to write efficient code accounting for hardware

- Performance analysis: computing and optimizing system performance

- Memory management: understanding of paging and caching mechanisms

Self-Assessment

This course was fundamental for my understanding of computer systems. I particularly appreciated:

Strengths:

- Theory/practice connection: MIPS assembly labs made abstract concepts tangible

- Hardware understanding: clear vision of what happens "under the hood"

- Optimization: ability to understand why certain code is faster

- Debugging: better understanding of errors (segfault, cache miss, etc.)

Difficulties encountered:

- MIPS assembly: syntax and conventions different from C

- Pipeline and hazards: abstract concepts requiring visualization

- Cache calculations: numerous formulas and special cases

Practical applications:

- Code optimization for embedded systems

- Understanding real-time constraints

- Choosing algorithms suited to the architecture

My Opinion

This course is essential for any engineer in computer science or embedded systems. Even in the era of high-level languages, understanding hardware architecture enables:

- Better performance: code optimized for cache and pipeline

- Effective debugging: understanding memory errors and slowdowns

- Technical decisions: selecting the right processor for an application

- Embedded systems: designing systems with strict constraints

Connections with other courses:

- Operating Systems (S5): virtual memory management, scheduling

- Microcontroller (S6): practical application on STM32

- Real-Time Systems (S8): timing constraints related to hardware

- Embedded Systems (S7): optimization for limited resources

Evolution of architectures:

Today, challenges have evolved:

- Multiprocessor: parallelism, complex cache coherence

- Heterogeneous: CPU + GPU + accelerators (TPU, NPU)

- Non-volatile memory: new technologies (3D XPoint, ReRAM)

- Security: Spectre, Meltdown → performance/security trade-offs

Moore's Law is slowing down, but innovation continues:

- 3D architecture (stacking)

- Near-memory computing (in-memory computing)

- Neuromorphic architectures

- Quantum computing (future)

Recommendations for success:

- Practice assembly: write MIPS code, analyze C disassembly

- Visualize: draw pipelines, caches, page tables

- Calculate: do and redo performance exercises

- Read specifications: processor datasheets (ARM, x86)

- Profile: use tools (perf, valgrind) to observe cache behavior

Professional applications:

This knowledge is used in:

- Compiler development: machine-specific optimizations

- Operating systems: schedulers, memory managers

- Video games: advanced optimizations for high FPS

- HPC (High Performance Computing): supercomputers

- IoT: resource-constrained microcontrollers

- Automotive: safety-critical real-time ECUs

- Security: hardware vulnerability analysis

In conclusion, this course provides the essential foundations for understanding how software interacts with hardware. It is an investment that pays off throughout one's career, as the fundamental principles (memory hierarchy, pipeline, cache) remain valid even as technologies evolve.

Course Documents

Here are the course materials in PDF format to deepen your understanding of computer hardware architecture:

Introduction to Architectures

Overview of computer architectures, historical evolution and fundamental concepts.

Physical Memory

Physical memory organization, memory types (RAM, ROM, Flash) and memory hierarchy.

Virtual Memory

Virtual memory management, paging, segmentation and address translation.

Cache Memory

How caches work, replacement policies, cache coherence and performance optimization.

Processor

Processor architecture, pipeline, instruction-level parallelism and hardware optimizations.